For your average fisherman who feels very insignificant in front of God, they are finding it difficult to understand the connetion between climate change and human activity. When people say changes in weather patterns are because of nature and not because of man, you really have to connect: if humans can become carbon-neutral, then God could act in a different set of ways. But God has to be there in the conversation somewhere. President Mohamed Nasheed of the Maldives NYT May 10 2009.

Monday, May 11, 2009

The Maldives, Climate Change and God

A great quote about the cultural complexities of acting on climate change. From the Maldives; islands in the Indian Ocean that may disappear and/or become highly vulnerable to storms with sea level rise.

Sunday, December 28, 2008

The Gas Tax - low hanging fruit for climate change action

This weekend the NYT has a duet of opinion pieces about climate change, the Saturday Editorial page and Friedman’s Op-Ed, both on the subject of the gasoline tax. Given the recent drop in gas prices levels, and the collective inefficiency of vehicles in the US, an increase in the gasoline tax seems the single most effective step we can take now towards reducing our emissions.

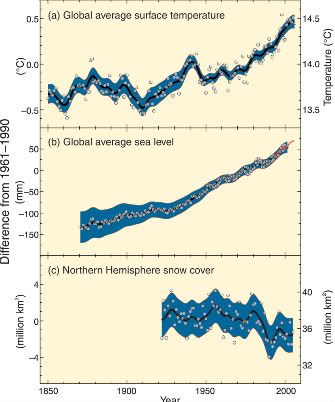

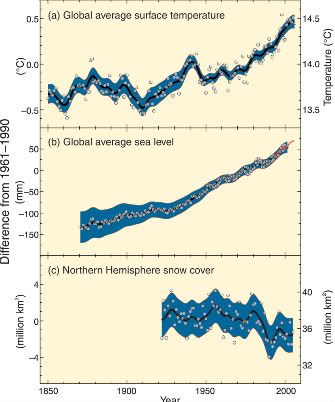

On BMG a few weeks ago, a fellow cape codder (PP) mentioned that he’s not sure he believes in climate change. That took a little bite out of my faith in humanity, or more realistically, made me start thinking seriously about scientists’ continuing difficulty in getting the message across. So since a picture is worth a thousand words: from the 2007 IPCC report:

Here's a figure about the rise in atmospheric CO2 concentrations and projections under different CO2 reduction scenarios (from Pacala et al 2004):

When I give talks to school classrooms, I do a little class participation exercise that goes like this: atmospheric CO2 was ~280 ppm (parts-per-million) prior to the industrial revolution a few centuries ago. It is now ~384 ppm. What do they think it should be for a sustainable level? They usually give me numbers in the 250-300 range. Then I show this figure, and point out that we’re running higher than the black line, business-as-usual (worst case scenario). Given the inertia of trying to move away from fossil fuels, CO2 is likely to double pre-industrial levels to 450-500ppm within their lifetimes with significant efforts. If we continue to do nothing it could very well reach as high as 700 ppm. This exercise seems to work well to get the message across.

Back to the NYT Op-Eds: There’s been a lot of dumping lately on the big three US automakers for not producing fuel efficient cars. But that’s revisionist history, over the last few decades Americans have been wanting those bigger SUVs creating the demand. We, the American consumers, are the other dancing partner in our gluttonous use of fossil fuels for transportation. The big three have been happy to oblige – SUVs have a big profit margin. Plus even Toyota has been in the big vehicle game. Sure they developed the Prius and some great hybrid technology, but they hedged their bets with the popular Tundra truck. There is simply no other policy action that would be as effective in reducing US fossil fuel emissions in the near future as increasing the gasoline tax. And it should be revenue neutral, using those funds to reduce income taxes to build popular support. From the NYT Editorial:

Personally I find it hard not to feel like a broken record on this subject of carbon taxes, but as a scientist I think its easy to forget that the public isn't looking at the data every day, and they're also thinking about many other important issues. Here's a great cartoon by Justin Bilicki (via the Union of Concerned Scientists ) capturing this sentiment.

And a nice quote to sum it up from Ray at NPR's Car Talk:

An increase in the Gasoline Tax is just one of the tools in the toolbox. It gets the biggest bang for effort in reducing climate change impact right now. This is just the beginning though: We're going to need many such tools to get this problem under control.

On BMG a few weeks ago, a fellow cape codder (PP) mentioned that he’s not sure he believes in climate change. That took a little bite out of my faith in humanity, or more realistically, made me start thinking seriously about scientists’ continuing difficulty in getting the message across. So since a picture is worth a thousand words: from the 2007 IPCC report:

Here's a figure about the rise in atmospheric CO2 concentrations and projections under different CO2 reduction scenarios (from Pacala et al 2004):

When I give talks to school classrooms, I do a little class participation exercise that goes like this: atmospheric CO2 was ~280 ppm (parts-per-million) prior to the industrial revolution a few centuries ago. It is now ~384 ppm. What do they think it should be for a sustainable level? They usually give me numbers in the 250-300 range. Then I show this figure, and point out that we’re running higher than the black line, business-as-usual (worst case scenario). Given the inertia of trying to move away from fossil fuels, CO2 is likely to double pre-industrial levels to 450-500ppm within their lifetimes with significant efforts. If we continue to do nothing it could very well reach as high as 700 ppm. This exercise seems to work well to get the message across.

Back to the NYT Op-Eds: There’s been a lot of dumping lately on the big three US automakers for not producing fuel efficient cars. But that’s revisionist history, over the last few decades Americans have been wanting those bigger SUVs creating the demand. We, the American consumers, are the other dancing partner in our gluttonous use of fossil fuels for transportation. The big three have been happy to oblige – SUVs have a big profit margin. Plus even Toyota has been in the big vehicle game. Sure they developed the Prius and some great hybrid technology, but they hedged their bets with the popular Tundra truck. There is simply no other policy action that would be as effective in reducing US fossil fuel emissions in the near future as increasing the gasoline tax. And it should be revenue neutral, using those funds to reduce income taxes to build popular support. From the NYT Editorial:

Americans did not buy enormous gas guzzlers just because Detroit marketed them relentlessly. They bought them because they wanted big cars — and because gas was cheap. If gas stays cheap, Americans would be less inclined to squeeze their families into a lithe fuel-efficient alternative.

Furthermore, even if the government managed to convert General Motors, Chrysler and Ford to the cause of energy efficiency, cheap gas could open the door for a competitor — Toyota, perhaps? — to take over the lucrative market for gas-chuggers, leaving Detroit’s automakers eating dust once again.

Americans have flirted with fuel-efficient cars before only to jilt them when gas prices fell. In the late 1970s, for instance, they spurned light trucks as gas prices doubled. But as gas prices declined between 1981 and 2005, the market share of sport-utility vehicles, pickups, vans and the like jumped from 16 percent to 61 percent of vehicle sales in the United States.

Personally I find it hard not to feel like a broken record on this subject of carbon taxes, but as a scientist I think its easy to forget that the public isn't looking at the data every day, and they're also thinking about many other important issues. Here's a great cartoon by Justin Bilicki (via the Union of Concerned Scientists ) capturing this sentiment.

And a nice quote to sum it up from Ray at NPR's Car Talk:

I'm sick of people whining about a lousy 50-cent-a-gallon tax on gasoline! I think its time has come, and I call on all non-wussy politicians to stand with me, because our country needs us.

An increase in the Gasoline Tax is just one of the tools in the toolbox. It gets the biggest bang for effort in reducing climate change impact right now. This is just the beginning though: We're going to need many such tools to get this problem under control.

Sunday, December 7, 2008

Now is the time for a Massachusetts Automobile Carbon Tax

Today’s Op-Ed column by NYT’s Friedman has an emphasis on coupling a carbon tax with the financial and now potential Detroit bailout plans. There finally is a bipartisan national sentiment that reducing our imported fossil fuel consumption is a necessary component of any plan for our Nation’s future.

With the recent decrease in fuel prices, now is the time to step up to the plate and create a plan for increasing taxes on fossils fuels. As we know, Massachusetts can play a leadership role for the nation with regards to policy on a variety of important matters (Health Care, Gay Marriage, hopefully clean energy production). This is an ideal time for our Massachusetts legislators to show their vision again. We know Obama’s campaign is committed to working on the climate change and national security issues and their direct relationship to imported fossil fuels. Massachusetts can lead the way, showing it is possible, and giving political capital to the ideas of reducing fossil fuel consumption through economic incentives.

This could start with something as simple as raising the gasoline tax in Massachusetts. Currently we are taxing at 41.9 cents per gallon, lower than most states (see map), and much lower than other progressive states such as California (67.1 cents), New York (60.9 cents), and even Detroit’s own Michigan (59.4). Friedman champions the idea of “neutral-revenue” carbon taxes, where all revenue gained is returned as income tax rebates/offsets. This is the key to carbon and gasoline taxes: make them politically palatable by making it clear that all of the increased revenue will return to the taxpayers:

More on the revenue-neutral idea: Nationally, carbon tax rebate checks could be sent out like stimulus checks (although this is perhaps a little too contrived for our new President). Alternatively, simply announce very publicly that the income tax percentage rate will be dropped by 0.4% this year (for example). This could be done in Massachusetts now. Raise the gas tax 25 cents this year (for example), and another 25 cents every year for four years (to start). This creates an immediate long-term incentive for consumers to continue buying efficient cars the next time the need one, phasing it in with a time-scale similar to the long life cycles of automobiles. With gas prices having dropped below $2 in Massachusetts, now is the time to create take action: citizens have certainly noticed the amazingly high prices of $4 a gallon, so 25 cents on $2 gasoline doesn’t seem unreasonable, especially if it offsets income taxes. The offsetting the income taxes part is important: those who buy efficient vehicles or drive less will save more because the reduction in income taxes is uniform – hence those using less than the average will be rewarded. It’s just like that economists’ saying: tax what you don’t want (fossil fuel consumption) not what you want (income!).

Legislators should resist the urge to use this as a revenue builder. Keep it separate from our current state gasoline tax, so this revenue-neutral part is obvious. The political capital is here now for this. If it’s done right (through the revenue-neutral idea), it will have bipartisan support. Our Govenor Deval Patrick commented on this on his live-blogging last summer:

He’s clearly sensitive to the political difficulties of “broad-based tax increases”. But this is where the need for the revenue-neutral idea should be paired with it. As Friedman, and those writing at the carbontax.org group, and others have pointed out, there has to be some economic (dis)incentives in order to decrease emissions. Compared to outlawing inefficient cars (talk about political difficulties), carbon and gasoline taxes are the most agile policy tool.

Footnotes: Diesel and heating oil are another interrelated problem. You don’t want everyone to switch to Diesel (if it is not taxed), so automobile diesel should be included. But you don’t want individual homeowners to suffer with higher heating bills unless it is coupled with a program for increased home insulation and heating efficiencies. Automobile diesel could be taxed similarly to gasoline, but home diesel distributors/sales would not be included in the short-term (first few years), until a coordinated home fuel efficiency program is implemented.

With the recent decrease in fuel prices, now is the time to step up to the plate and create a plan for increasing taxes on fossils fuels. As we know, Massachusetts can play a leadership role for the nation with regards to policy on a variety of important matters (Health Care, Gay Marriage, hopefully clean energy production). This is an ideal time for our Massachusetts legislators to show their vision again. We know Obama’s campaign is committed to working on the climate change and national security issues and their direct relationship to imported fossil fuels. Massachusetts can lead the way, showing it is possible, and giving political capital to the ideas of reducing fossil fuel consumption through economic incentives.

This could start with something as simple as raising the gasoline tax in Massachusetts. Currently we are taxing at 41.9 cents per gallon, lower than most states (see map), and much lower than other progressive states such as California (67.1 cents), New York (60.9 cents), and even Detroit’s own Michigan (59.4). Friedman champions the idea of “neutral-revenue” carbon taxes, where all revenue gained is returned as income tax rebates/offsets. This is the key to carbon and gasoline taxes: make them politically palatable by making it clear that all of the increased revenue will return to the taxpayers:

Many people will tell Mr. Obama that taxing carbon or gasoline now is a “nonstarter.” Wrong. It is the only starter. It is the game-changer. If you want to know where postponing it has gotten us, visit Detroit. No carbon tax or increased gasoline tax meant that every time the price of gasoline went down to $1 or $2 a gallon, consumers went back to buying gas guzzlers. And Detroit just fed their addictions — so it never committed to a real energy-efficiency retooling of its fleet. R.I.P.

If Mr. Obama is going to oversee a successful infrastructure stimulus, then it has to include not only a tax on carbon — make it revenue-neutral and rebate it all by reducing payroll taxes — but also new standards that gradually require utilities and home builders in states that receive money to build dramatically more energy-efficient power plants, commercial buildings and homes. This, too, would create whole new industries.

More on the revenue-neutral idea: Nationally, carbon tax rebate checks could be sent out like stimulus checks (although this is perhaps a little too contrived for our new President). Alternatively, simply announce very publicly that the income tax percentage rate will be dropped by 0.4% this year (for example). This could be done in Massachusetts now. Raise the gas tax 25 cents this year (for example), and another 25 cents every year for four years (to start). This creates an immediate long-term incentive for consumers to continue buying efficient cars the next time the need one, phasing it in with a time-scale similar to the long life cycles of automobiles. With gas prices having dropped below $2 in Massachusetts, now is the time to create take action: citizens have certainly noticed the amazingly high prices of $4 a gallon, so 25 cents on $2 gasoline doesn’t seem unreasonable, especially if it offsets income taxes. The offsetting the income taxes part is important: those who buy efficient vehicles or drive less will save more because the reduction in income taxes is uniform – hence those using less than the average will be rewarded. It’s just like that economists’ saying: tax what you don’t want (fossil fuel consumption) not what you want (income!).

Legislators should resist the urge to use this as a revenue builder. Keep it separate from our current state gasoline tax, so this revenue-neutral part is obvious. The political capital is here now for this. If it’s done right (through the revenue-neutral idea), it will have bipartisan support. Our Govenor Deval Patrick commented on this on his live-blogging last summer:

Danny wrote about the gas tax. I am not hostile to the gas tax, but it's not my first choice. But I think we owe the public every attempt and strategy to get savings and efficiencies out of the systems before we go out asking for broad-based tax increases. I also question whether the gas tax will produce the level of new revenues that have been projected, when we are at the same time pursuing strategies to reduce emissions and gain fuel efficiencies.

He’s clearly sensitive to the political difficulties of “broad-based tax increases”. But this is where the need for the revenue-neutral idea should be paired with it. As Friedman, and those writing at the carbontax.org group, and others have pointed out, there has to be some economic (dis)incentives in order to decrease emissions. Compared to outlawing inefficient cars (talk about political difficulties), carbon and gasoline taxes are the most agile policy tool.

Footnotes: Diesel and heating oil are another interrelated problem. You don’t want everyone to switch to Diesel (if it is not taxed), so automobile diesel should be included. But you don’t want individual homeowners to suffer with higher heating bills unless it is coupled with a program for increased home insulation and heating efficiencies. Automobile diesel could be taxed similarly to gasoline, but home diesel distributors/sales would not be included in the short-term (first few years), until a coordinated home fuel efficiency program is implemented.

Tuesday, July 22, 2008

I’ve been attending the US-Ocean Carbon and Biology Workshop in Woods Hole this week (see webcast during day). Here’s some highlights and thoughts that are of general interest.

There was a report about how the rate of CO2 emissions was increasing about 4% per year from 1960-1979, decreased to 1.5% per year from the 1980’s to 1999, and in this decade (since 2000) has increased again to 4% per year. This is obviously alarming because it shows that we are not any making progress at all in reducing CO2 emissions: things are getting worse not better. Also, last year was the first year that China has equaled or replaced the US as the nation with the highest CO2 emissions (it’s close enough to be difficult to tell if it is equal to or greater than). Don’t fret though, on a per capita basis, we’re still winning the CO2 emission game by a long shot because we have a third as many people as China.

I thought it was also interesting that today in the NYT there’s also a Freakonomics blog post about “Financial literacy” where you can take a brief quiz and it talks about how a scary number of Americans get many of these questions wrong. For example Question #1 is:

I think these two pieces of information make an interesting juxtaposition. Maybe the CO2 rising doesn’t seem as alarming as it should because everything else in our lives is increasing. Population, the economy, traffic, computer speed… We’re used to things increasing. And this kind of acceleration is usually considered a good thing. There's even an urban myth that compounding interest was hailed by Einstein as humanity’s greatest invention (this appear to be a made up quote). With this perspective, maybe its not so bad that CO2 goes up 4% a year, basically increasing with compounding interest like a savings account?

Yikes is all I can say. And I can’t say it sincerely enough, I think I’d have to scream it to feel like I’m doing justice to the sentiment. Elemental cycles are not mutual funds. We started at 280 ppm in the 1800's (ppm=parts per million) and we’re up to 382 this year. Most think there’s no way we can get our emissions under control before we hit 500, and we’re beating the worse case scenarios already to surpass that (see above). We’re talking about more than doubling the CO2 in the atmosphere. Elements aren’t money. They have mass, I hate to say it, but they’re real. Money used to be backed by a real gold standard, but that was done away with - there isn’t enough gold out there anymore. The giant pool of money is (usually) increasing. That’s easy, its just digits on a bunch of hard drives somewhere. Money doesn’t follow conservation of mass (which is a discussion point in and of itself). The greenhouse gas and climate change problem is almost entirely caused by taking oil or coal buried deep in the ground and burning it and putting that carbon in the air. Not only do we have to stop putting the carbon it up there, we will likely have to figure out ways to pull some out of the atmosphere as well, “sequestering it” as it is known.

Last week Al Gore laid out an ambitious plan to stop become independent of fossil fuels by 2018. It’s very ambitious considering how broad the changes will have to be throughout our society. But, it is humbling to realize the kind of action that we need to actually solve the climate change problem. Our society has a choice: Do we decide it's too hard and pick a lesser path, or do we say that’s what we have to do and figure out how to get it done.

I particularly like that Gore is trumpeting this policy approach that we've talked about [before: http://www.bluemassgroup.com/showDiary.do?diaryId=11381]

cross post: bluemassgroup

There was a report about how the rate of CO2 emissions was increasing about 4% per year from 1960-1979, decreased to 1.5% per year from the 1980’s to 1999, and in this decade (since 2000) has increased again to 4% per year. This is obviously alarming because it shows that we are not any making progress at all in reducing CO2 emissions: things are getting worse not better. Also, last year was the first year that China has equaled or replaced the US as the nation with the highest CO2 emissions (it’s close enough to be difficult to tell if it is equal to or greater than). Don’t fret though, on a per capita basis, we’re still winning the CO2 emission game by a long shot because we have a third as many people as China.

I thought it was also interesting that today in the NYT there’s also a Freakonomics blog post about “Financial literacy” where you can take a brief quiz and it talks about how a scary number of Americans get many of these questions wrong. For example Question #1 is:

1. Suppose you had $100 in a savings account and the interest rate was 2 percent per year. After 5 years, how much do you think you would have in the account if you left the money to grow?

a. More than $102

b. Exactly $102

c. Less than $102

d. Do not know

I think these two pieces of information make an interesting juxtaposition. Maybe the CO2 rising doesn’t seem as alarming as it should because everything else in our lives is increasing. Population, the economy, traffic, computer speed… We’re used to things increasing. And this kind of acceleration is usually considered a good thing. There's even an urban myth that compounding interest was hailed by Einstein as humanity’s greatest invention (this appear to be a made up quote). With this perspective, maybe its not so bad that CO2 goes up 4% a year, basically increasing with compounding interest like a savings account?

Yikes is all I can say. And I can’t say it sincerely enough, I think I’d have to scream it to feel like I’m doing justice to the sentiment. Elemental cycles are not mutual funds. We started at 280 ppm in the 1800's (ppm=parts per million) and we’re up to 382 this year. Most think there’s no way we can get our emissions under control before we hit 500, and we’re beating the worse case scenarios already to surpass that (see above). We’re talking about more than doubling the CO2 in the atmosphere. Elements aren’t money. They have mass, I hate to say it, but they’re real. Money used to be backed by a real gold standard, but that was done away with - there isn’t enough gold out there anymore. The giant pool of money is (usually) increasing. That’s easy, its just digits on a bunch of hard drives somewhere. Money doesn’t follow conservation of mass (which is a discussion point in and of itself). The greenhouse gas and climate change problem is almost entirely caused by taking oil or coal buried deep in the ground and burning it and putting that carbon in the air. Not only do we have to stop putting the carbon it up there, we will likely have to figure out ways to pull some out of the atmosphere as well, “sequestering it” as it is known.

Last week Al Gore laid out an ambitious plan to stop become independent of fossil fuels by 2018. It’s very ambitious considering how broad the changes will have to be throughout our society. But, it is humbling to realize the kind of action that we need to actually solve the climate change problem. Our society has a choice: Do we decide it's too hard and pick a lesser path, or do we say that’s what we have to do and figure out how to get it done.

I particularly like that Gore is trumpeting this policy approach that we've talked about [before: http://www.bluemassgroup.com/showDiary.do?diaryId=11381]

[Gore] said the single most important policy change would be placing a carbon tax on burning oil and coal, with an accompanying reduction in payroll taxes.

cross post: bluemassgroup

Sunday, May 4, 2008

Gas-Tax Holiday Roundly Rejected: "The dumbest thing I've heard in a long time".

A week ago on BMG we had a lively discussion about what is now referred to as the McCain-Clinton "Gas Tax Holiday". We preceded the pundits by a few days, as this became a major story this week. This idea was pretty much universally rejected by Economists, Democrats, and Republicans this week. The criticisms come from all angles: Environmentally this hurts our fledgling efforts at reducing fossil fuel emissions when we are already exceeding worse case scenarios for emissions; Economically the savings, an estimated $28 per family, would like not even reach consumers because prices would stay high due to demand and the oil companies would actually get those funds as a result; Politically, this is pure pandering to the voter since no one thinks the policy is a good one, nor is Congress considering or willing to consider this "Gas Tax Holiday". I list a number of links here from pundits describing this:

Mayor Bloomberg:

Gail Collins: A funny and sarcastic angle on this:

Paul Krugman: A Princeton Economist and rabid Clinton supporter (one of my favorite columnists for his Iraq war stance, but now I find him rather incoherent lately) who includes the sentence that the Gas Tax Holiday is a bad idea, and has also said so on his blog. I wonder if he's hoping for a Clinton administration cabinet position. He says:

Thomas Friedman:

NYT editorial "The Gas-Guzzler Gambit" on May 1st:

Salon's Alex Koppelman:

And the NYT had an article this week about how the high gas prices are creating significantly more demand for smaller fuel efficient vehicles. In other words, the high prices are working - we're starting to get more efficient (there's a long way to go though).

Finally we have a real policy issue difference between the candidates, and one that touches on the critical problems energy policy, national security and climate change. I think the Obama campaign should be more pointed in their response to the McCain-Clinton Gas Tax Holiday. After all if there's consensus that this is a useless policy, what does it mean that McCain and Clinton are basically trying to buy voters' support for a $28 that they will most likely not even get? Isn't that more than a little bit condescending to the voters? I've lived in the Midwest, people there are not dumb, but they may feel alienated from the East and West coast (rightly so oftentimes). As the pundits have pointed out: this just a case of Washington politics trying to pander to those midwest voters, not provide meaningful policies and vision.

Pundits: It's time to step up to the plate. Ask Clinton and McCain why they are calling for a gas-tax holiday that the experts roundly criticize as a bad idea. Ask Clinton and McCain if they really think they can trick voters with this bad policy, and does that mean they are condescending to the voters by not offering real solutions to our energy and environmental problems.

Mayor Bloomberg:

"It's about the dumbest thing I've heard in an awful long time, from an economic point of view," Bloomberg told reporters at City Hall. "We're trying to discourage people from driving and we're trying to end our energy dependence ... and we're trying to have more money to build infrastructure."

Gail Collins: A funny and sarcastic angle on this:

All this actually tells us something about the Democratic candidates, which has nothing to do with fuel prices. Obama believes voters want a sensible, less-divisive political dialogue, that the whole process can become more honorable if the right candidate leads the way. Hillary really doesn’t buy that. She has principles, but she doesn’t believe in principled stands. She thinks that if she can get elected, she can do great things. And to get there, she’s prepared to do whatever. That certainly includes endorsing any number of meaningless-to-ridiculous ideas. (See: her bill to make it illegal to desecrate an American flag.)

Paul Krugman: A Princeton Economist and rabid Clinton supporter (one of my favorite columnists for his Iraq war stance, but now I find him rather incoherent lately) who includes the sentence that the Gas Tax Holiday is a bad idea, and has also said so on his blog. I wonder if he's hoping for a Clinton administration cabinet position. He says:

"To be clear, both Democratic candidates have been saying things they shouldn’t; Hillary Clinton shouldn’t have endorsed the bad idea of a gas tax holiday."

Thomas Friedman:

The McCain-Clinton gas holiday proposal is a perfect example of what energy expert Peter Schwartz of Global Business Network describes as the true American energy policy today: “Maximize demand, minimize supply and buy the rest from the people who hate us the most.” Good for Barack Obama for resisting this shameful pandering.

NYT editorial "The Gas-Guzzler Gambit" on May 1st:

Neither Mrs. Clinton nor Mr. McCain have explained the inconsistency in their positions. We know pandering when we see it. We also know that suspending the gas tax for the summer won’t solve this country’s energy problems or even reduce the price of gas.

Salon's Alex Koppelman:

As I've said before, Clinton deserves the hits she's taking on this issue -- I've yet to see a single expert who thinks her proposal would do Americans any good... One of the principal objections to the holiday proposal has been that because the tax is not actually collected at the pump, there's no reason to believe that the oil companies will actually pass on to consumers the full savings from the suspension of the tax.

And the NYT had an article this week about how the high gas prices are creating significantly more demand for smaller fuel efficient vehicles. In other words, the high prices are working - we're starting to get more efficient (there's a long way to go though).

Finally we have a real policy issue difference between the candidates, and one that touches on the critical problems energy policy, national security and climate change. I think the Obama campaign should be more pointed in their response to the McCain-Clinton Gas Tax Holiday. After all if there's consensus that this is a useless policy, what does it mean that McCain and Clinton are basically trying to buy voters' support for a $28 that they will most likely not even get? Isn't that more than a little bit condescending to the voters? I've lived in the Midwest, people there are not dumb, but they may feel alienated from the East and West coast (rightly so oftentimes). As the pundits have pointed out: this just a case of Washington politics trying to pander to those midwest voters, not provide meaningful policies and vision.

Pundits: It's time to step up to the plate. Ask Clinton and McCain why they are calling for a gas-tax holiday that the experts roundly criticize as a bad idea. Ask Clinton and McCain if they really think they can trick voters with this bad policy, and does that mean they are condescending to the voters by not offering real solutions to our energy and environmental problems.

Sunday, April 27, 2008

willis music video

I've always joked that music inspires my science. Well I've written two blogs while waiting for this music video to be processed in various ways tonight. Here it is: Penguin Fight Song

willis is our rock band. Apparently, we write deep songs about penguins. Bono eat your heart out.

willis is our rock band. Apparently, we write deep songs about penguins. Bono eat your heart out.

Open Access in Environmental and Earth Sciences

A simple question: If you wanted to see the scientific papers on the state of Global Warming, or the cutting-edge papers directly addressing how society should respond (note: I can't believe this paper isn't open access, try it, follow the link), couldn't you just google scholar them and read them? Without a University or individual subscription, the answer is shockingly: no.

There is a movement afoot called the "Open Access" movement to allow the scientific literature to be accessible to anyone without subscription fees. The notion is simple: research is most often typically paid for by the tax dollars of nations of the world. That research should be freely available to the citizens who paid for it. Instead, much of that research is written in scholarly manuscripts published by private publishers who own the copyright (Note: the publishers own the copyright, not the authors) and is sold on a subscription basis to scientific libraries and interested individuals.

All that seems fine at first glance, and has largely been the business model for many decades. However, what about the parents of a sick child who want to examine the research papers themselves? Should they have to pay $30 for every article to a private (for profit) publisher? You can see the problem. This has been exacerbated by the increasing availability of the internet: many journals are becoming electronic only, or combination electronic/paper delivery. The electronic component is leased annually as long as subscription dues are paid. Unsubscribe, and the library typically loses electronic access to all the years it was a subscriber.

There's been a real tussle over this, and the Open Access movement has risen similar to the open source movement in computing (e.g. Linux), but with differences too, in particular, real editorial costs associated with publishing a scientific journal that make up the fixed costs that need to be considered. Public Library of Science (PLOS.org) is the flagship of this movement.

Earth sciences has lagged behind considerably. Our most exciting papers most often come out in Nature or Science (both are not open access, the former is For-Profit), and most of our smaller specialized journals are either Elsevier (for profit company that owns much of the scientific literature), or by the American Geophysical Union that has not adopted open access. There is Biogeosciences that has real open access, and Limnology and Oceanography, my favorite journal by far, that has pay-extra open access as an option.

The debate is starting to come to Earth and Ocean sciences. Pete Jumars, former editor of Limnology and Oceanography, wrote a truly excellent Limnology and Oceanography Bulletin piece about this recently. And interestingly, he seemed to be interacting with bloggers about it in the years before likely while formulating ideas. He seems to have come around in the intervening years between writing bloggers and writing his article. But many of my colleagues express reservations about open access, arguing that if the costs are moved to the author (e.g. $2500 author charges to publish in PLOS) then only researchers at major Universities with research grants will be able to publish (and similarly creating a problem for colleagues in third world nations). It is true the economics of open access are fundamentally different and challenging.

Yet, no matter how you view it public access to tax-dollar funded scientific research is clearly the right thing to do. Do we avoid doing something that is right because it is different and challenging? No. It will be interesting to see how this evolves in the coming years.

There is a movement afoot called the "Open Access" movement to allow the scientific literature to be accessible to anyone without subscription fees. The notion is simple: research is most often typically paid for by the tax dollars of nations of the world. That research should be freely available to the citizens who paid for it. Instead, much of that research is written in scholarly manuscripts published by private publishers who own the copyright (Note: the publishers own the copyright, not the authors) and is sold on a subscription basis to scientific libraries and interested individuals.

All that seems fine at first glance, and has largely been the business model for many decades. However, what about the parents of a sick child who want to examine the research papers themselves? Should they have to pay $30 for every article to a private (for profit) publisher? You can see the problem. This has been exacerbated by the increasing availability of the internet: many journals are becoming electronic only, or combination electronic/paper delivery. The electronic component is leased annually as long as subscription dues are paid. Unsubscribe, and the library typically loses electronic access to all the years it was a subscriber.

There's been a real tussle over this, and the Open Access movement has risen similar to the open source movement in computing (e.g. Linux), but with differences too, in particular, real editorial costs associated with publishing a scientific journal that make up the fixed costs that need to be considered. Public Library of Science (PLOS.org) is the flagship of this movement.

Earth sciences has lagged behind considerably. Our most exciting papers most often come out in Nature or Science (both are not open access, the former is For-Profit), and most of our smaller specialized journals are either Elsevier (for profit company that owns much of the scientific literature), or by the American Geophysical Union that has not adopted open access. There is Biogeosciences that has real open access, and Limnology and Oceanography, my favorite journal by far, that has pay-extra open access as an option.

The debate is starting to come to Earth and Ocean sciences. Pete Jumars, former editor of Limnology and Oceanography, wrote a truly excellent Limnology and Oceanography Bulletin piece about this recently. And interestingly, he seemed to be interacting with bloggers about it in the years before likely while formulating ideas. He seems to have come around in the intervening years between writing bloggers and writing his article. But many of my colleagues express reservations about open access, arguing that if the costs are moved to the author (e.g. $2500 author charges to publish in PLOS) then only researchers at major Universities with research grants will be able to publish (and similarly creating a problem for colleagues in third world nations). It is true the economics of open access are fundamentally different and challenging.

Yet, no matter how you view it public access to tax-dollar funded scientific research is clearly the right thing to do. Do we avoid doing something that is right because it is different and challenging? No. It will be interesting to see how this evolves in the coming years.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)